Fundamental Blueprint Practices

Learn few basic things that will greatly improve your visual scripting

Blueprint as a programming language

-

The best feature of blueprints: it allows us to start coding video games logic without any programming knowledge.

-

The worst feature of blueprints: it allows us to start coding video games logic without any programming knowledge.

There's no accidental copy-pasting text above. Visual scripting is a huge step forward giving people freedom of creation. Nowadays everyone can create a new project and start with prototyping their idea. Learning engine and programming on the go.

The only problem is that official documentation fails to explain anything beyond "how to click into blueprints". If you are lucky, you could already encounter people or YouTube videos explaining to you a few basic concepts of "engineering thinking".

-

How to avoid killing your framerate and start asking yourself "how much performance do these scripts cost us"?

-

How to avoid creating "gigabyte blueprints" - scripts that reference half of the game and you don't even know it, so you end up loading half of the game while opening Player's blueprint.

-

Concepts of code architecture and Object-Oriented Programming. These what you touch every day, but probably you didn't know the name for it.

These are relatively easy things to grasp if someone explains it to you, but it can be a lot of new concepts to "digest" at once. No worries, you can simply learn one thing, use it to compose better blueprints, repeat it, improve your skills. And come back to this resource to learn the next things.

And don't let anybody fool you. Your job title maybe not a "gameplay programmer" and you may be unable to use classic programming languages yet, but blueprint visual scripting is still programming.

Official treasures

Epic did a great job of explaining many things about blueprint lately, although these materials are scattered on their sites.

This is a convenient list for you. This wiki guide is going to repeat and rephrase a lot of advice from official materials, you can approach it any order.

Blueprints In-depth - Part 1: https://youtube.com/watch?v=j6mskTgL7kU

Blueprints In-depth - Part 1: https://youtube.com/watch?v=j6mskTgL7kU

Blueprints In-depth - Part 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0YMS2wnykbc

Blueprints In-depth - Part 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0YMS2wnykbc

Blueprints: Blending System Architecture and Creativity: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gz1ryNs8S04

Blueprints: Blending System Architecture and Creativity: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gz1ryNs8S04

Unofficial treasures

Unreal Directive

The most important stuff:

Blueprints vs. C++: How They Fit Together and Why You Should Use Both: https://youtube.com/watch?v=VMZftEVDuCE

Blueprints vs. C++: How They Fit Together and Why You Should Use Both: https://youtube.com/watch?v=VMZftEVDuCE

Critical issues you can easily avoid

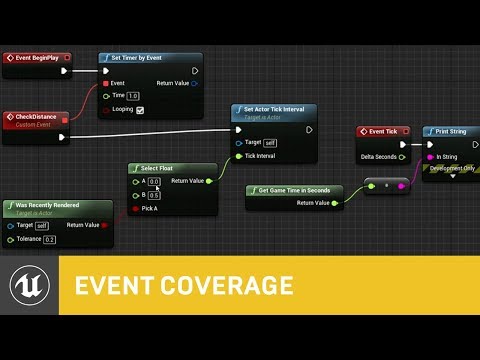

Aim for using Events instead of Ticks, Timers or Delays. If it's impossible, use Timers instead of Delay and reduce ticking as much as possible

You should always bind actions to some single-frame Events like BeginPlay, Event Dispatchers like OnTakeAnyDamage, or your custom BlueprintImplementableEvents or Delegates created in C++. Using Latent Actions to wait for some gameplay action is bad not only in terms of performance. It can easily generate a lot of bugs, because usually you have no guarantee how much time you have to wait.

However, Delays are convienient if you have to wait just 1 frame.

Taking into account the disadvantages delay nodes have, consider using the Better Delays plugin:

If you have to wait a specific amount of time, Timers are better than Delays because you have more control with them - you can cancel or pause them if needed.

It is also a good practice to clear timers when the object is destroyed (because in fact Timers are handled by the World, not by the Object. So the timer might be still active even if the Actor/Object that started it is already destroyed).

Note: You should never use the Set Timer by Function Name function in blueprints. It's an unsafe practice. If someone would change the name of the function, this timer will stop working.

Use the Set Timer by Event function instead.

Performing a lot of operations on blueprint Tick is one of the main reasons for the low performance of your gameplay code. Plus it makes blueprint messy and difficult to maintain if you call a lot of things on Tick.

However, Ticks are usually better than looped Timers - first of all, you are guaranteed it won't be executed after an Object is destroyed, because Ticks are handled by the Object, but Timers are handled by the World. You can also easily stop Object's ticking from another class.

But you should disable Ticks when they're no longer needed or increase their intervals if possible. You can do that by using those functions.

Also, disable StartWithTickEnabled in Class Defaults, if you don't need Tick from the start of the Actor/ActorComponent.

However, looped Timers are better than Ticks when you need a constant delta time. Delta time in Tick will be dependend on the time dilation in its Owner or in World.

Pure functions - calculations of blueprint node networks aren't magically cached

One of the common assumptions of new blueprint users is that result of blueprint operations is somewhat automagically cached in this network. It's not. If you'd connect a wire to a network of nodes doing some calculation, these calculations are performed as many times as you would connect wires to it. You need to save the result to a variable (preferably a local variable) of operations after calling it for the first time and get this variable value later.

More about the threats from pure functions:

Avoid using "Get All Actors of Class"

It's an expensive function. Basically iterates on all actors in the world, checking every single one of them, if it matches your criteria. A good programmer almost never uses it, and then mostly for quick debugging purposes.

To obtain needed actors, simply register your actor to some manager when an actor appears in the world. In blueprints, you'd call it on Begin Play most of the time. Use your custom manager class or extend class like Game Mode for this purpose.

If you've got the C++ project already, consider defining your manager in C++. Especially that Programming Subsystems are perfect for this purpose.

You can also use UE plugins for that, for instance: Dynamic Octree.

Avoid using Child Actor Components

Child Actor Components can lead to buggy behaviors in terms of the initialization or replication. They can be used for cosmetic-only actors for the level design, but if you want to spawn some more complex Actors like Player's items, it's better to use "SpawnActorFromClass" node, attach it to the specific component and socket, and destroy on Onwer's EndPlay.

Avoid using Level Blueprints

Although Level Blueprints are fine for testing your implementations in your test levels, they can easily become very messy because of their limited support of OOP principles.

What to use instead of Level Blueprints?

- Other classes from the Unreal Engine Gameplay Framework: GameInstance, WorldSettings, GameModeBase, GameStateBase, PlayerState — the choice depends on what exactly you want to implement.

- Unreal Subsystems (preferably derived from UWorldSubsystem) - although they require C++ programming

- External plugins like FlowGraph or Arcweave

A more detailed article about object references in Blueprints:

Avoid casting to blueprint classes

As official documentation Balancing Blueprint and C++ says

Avoid Casting to Expensive Blueprints: Whenever you cast to a Blueprint class BP\\_A (or declare it as a variable type on a function or another Blueprint) from BP\\_B it creates a load dependency on that Blueprint. Then if BP\\_A references four large Static Meshes and 20 sounds, every time you load BP\\_B it will have to load four large Static Meshes and 20 sounds, even if the cast would fail. This is one of the primary reasons it’s essential to have either native base classes or minimal Blueprint base classes that define the important functions and variables. Then, you should make your expensive Blueprints as child classes.

How to avoid that?

-

Try to cast to blueprints that you know are already loaded into memory.

-

Use event dispatcher instead of calling a function on the target blueprint.

-

Use interfaces.

-

Use components containing specific features i.e. Inventory Component instead of putting this code into the MyShopkeeper blueprint.

-

Use systems identifying actor instances by something else than class, i.e. Gameplay Tags and IGameplayTagAssetInterface.

-

Create native C++ base classes - it can be crazy useful if you write most of your logic in blueprints.

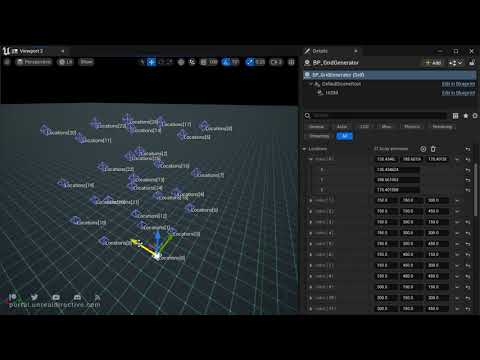

Don't create Actors or Components if you only need to point a specific location in the level. Use Vectors or Transforms with "Show 3D Widget" instead

You can noticeably increase the Map/Actor size if you create too many objects which do nothing more than pointing a location or a transform. Instead, enable Show 3D Widget on Vector and Transform variables to allow a direct manipulation from within the level viewport.

Show 3D Widget: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mp-9uec2cY4

Show 3D Widget: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mp-9uec2cY4

Learn about hard references, soft references, and reference chain

-

Hard references are the default type object reference in the blueprint, so you already use it all the time. If blueprint A references to blueprint B, opening A in the editor or loading it in-game automatically loads blueprint B.

-

Reference chain. If blueprint A loads blueprint B automatically, this also means that blueprint B loads all its referenced blueprints automatically and all the assets used by those blueprints. That's why its super-easy to mess this up. If your Player Blueprint references all game systems directly, loading this blueprint will load all the game systems and assets used by these systems. So you end up loading gigabytes of data and waiting a minute to open a Player Blueprint. No worries, designers in professional studios often do this mistake.

Solving this requires using 2 "solutions" all the time.

-

Soft references. It's the way to connect things without automatically loading references. You have to manually call loading it only when it's needed, i.e. loading sound or cutscene just before you want to play it, not at the beginning of the game.

-

Clean code architecture. This is a big topic, but a fundamental part of the programmer's work.

More detailed articles about object references in Blueprints:

Demystifying Soft Object References: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K0ENnLV19Cw

Demystifying Soft Object References: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K0ENnLV19Cw

Clean code architecture

You need to think about how to decouple things: isolate systems, features, classes and assets. It could be initially difficult to understand which way of doing things is clean. It will come by practice and constant thinking "is it proper way of doing things? can this be improved?".

In properly implemented game Player Blueprint does never know about the existence of a door or shopkeeper. Interaction of player with door or shopkeeper is executed by the Interaction Component. This component doesn't know about the existence of any actor class using it, i.e. Player, Door, Shopkeeper. You could eventually create enums or gameplay tags to define interaction types.

Actionable examples of managing dependencies

Managing dependencies is much eaiser than fully decoupling everything in a game, and a good place to start. Here are some examples:

- MyPlayerController is dependent on MyCharacter. MyCharacter shouldn't reference MyPlayerController. Referencing Native classes are fine. Referencing MyCharacter in MyPlayerController is fine, but try to reference a native/parent class if possible

- Try to avoid Referencing HUD/widget in game code. In general the HUD 'sits on top of the game' listening/bind for changes such as Health, EquippedWeapon, and the HUD can be swapped out without breaking the game.

- Components should be actor agnostic and not be dependent on a specific owner. HealthComponent shouldn't reference MyCharacter. HealthComponent can reference Native Actor, such as binding to Actor's OnAnyDamage, and MyCharacter can reference HealthComponent because it is already dependent on it.

For more information see Ari's Unreal Code Reviews.

For intermediate examples see UE Modules.

For more advanced examples see Lyra Sample Game.

I'm a game dev not an OOP nerd, why should I care about this? Mark Craig's Asset Dependency Chains: The Hidden Danger | UE Fest. TLDR Make your game easy to read, extend, find & fix bugs, and avoid needing 300GB of ram to package the project due to circular dependencies.